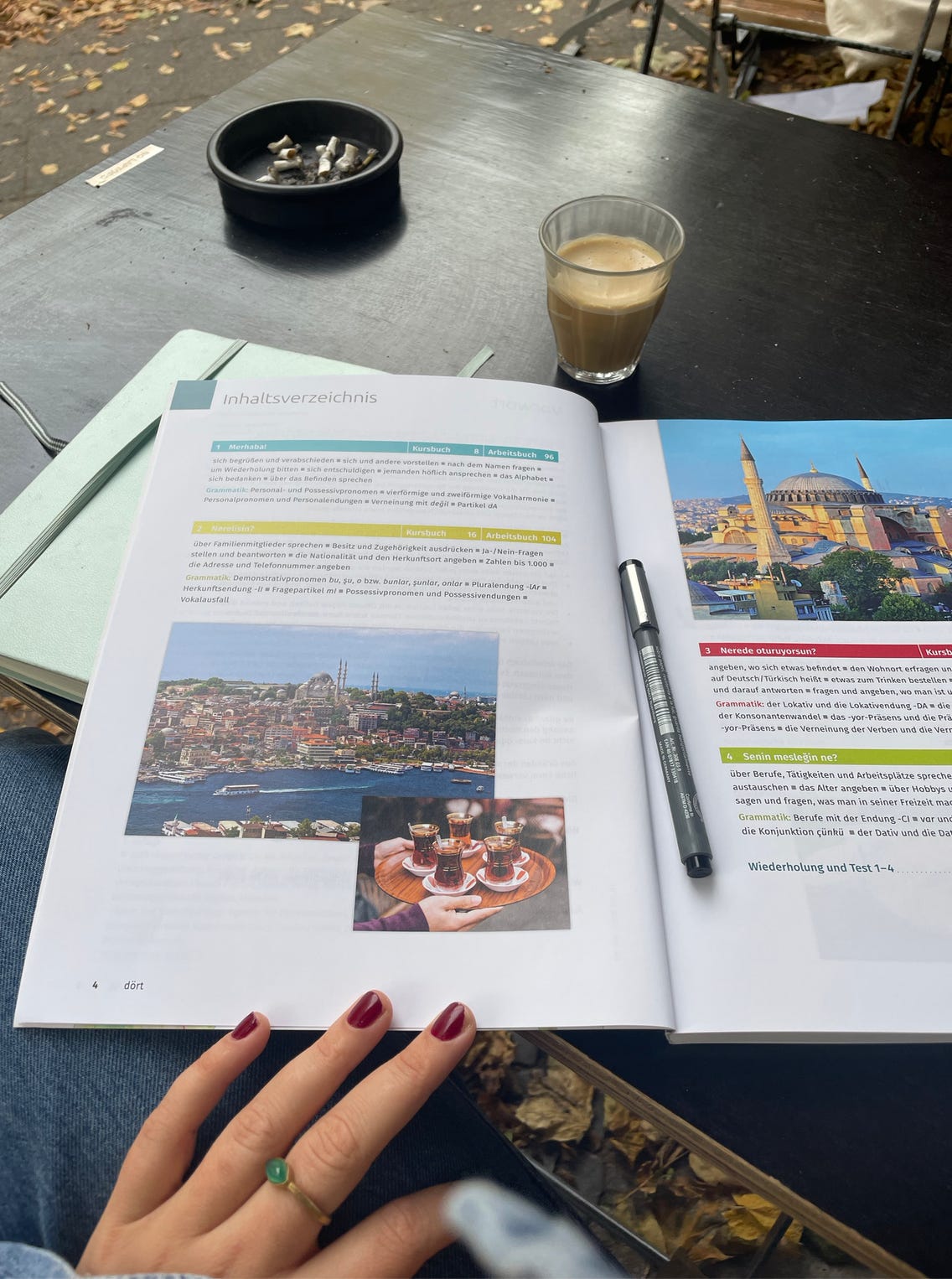

“Iyi şanslar!” the bookseller says as he hands me the Turkish A1 book I ordered. Upon seeing the puzzled look on my face, he explains: “It means good luck.”

“I’m only starting my course tomorrow,” I reply, apologetically. “I don’t know anything yet!”

With the book under my arm, I leave the bookshop in Berlin’s Neukölln district1 - and go to the bakery around the corner to get some gözleme. I’ve been craving this spinach-and-feta-filled flatbread and it gets me excited for my upcoming trip to Türkiye. Vorfreude, as the Germans call it.

Looking up at the breakfast menu, which shows faded pictures of plates of olives, cheese, sesame rings and cups of tea, it dawns on me that the only Turkish words I know are food-related: simit, döner, çay. I don’t even know how to say thank you.

***

An hour later, I press play on the first audio exercise and find myself completely lost. Given that this is a beginners course, I assume the conversation involves some “how are yous” and “what’s your names”, but aside from the greeting merhaba I cannot make out any of the words. I hit rewind, then rewind again. I am starting from zero.

I always thought I had a knack for languages, but the truth is, I’ve only ever studied languages that are similar to my mother tongue (Dutch), allowing me to improvise my way through. This was the case for French and German, which I learned in school, as well as Spanish and Italian, which I don’t actually speak but understand well enough to make my way around. As for English, I’ve never had to study it actively, I just learned by osmosis. I joke that my English education was watching a lot of Gossip Girl when I was 13, which, though not the whole truth, is a pretty solid explanation.

It’s humbling to learn a language you have no frame of reference for. You see the words on the page but you don’t know how to pronounce them, let alone how to use them in a sentence or what they might mean. 2

***

I moved from Amsterdam to Berlin four years ago, in October 2020. (All big changes in my life always seem to happen in October — but that’s a story for another day.)

My most conservative standpoint, I say half-jokingly, is that people should (at least try to) learn the language of the place they live in. It bothers me when I go back home and see train station signs written in English first, Dutch second, or a barista automatically takes my order in English. When I’m in the Netherlands I want to do things I can’t do while living abroad; browse HEMA and buy something I don’t need (most likely nail polish); eat Surinamese food (roti roll with tempeh, please); have a beer at a bruin café (a vaasje, not the German half-liter that goes lukewarm before you finish even half of it); ride on the back of someone’s bicycle; speak the language I grew up speaking.

In Berlin, as in Amsterdam, many expats don’t learn the language. There is simply no incentive; English is the lingua franca at their (tech) jobs and many locals speak English fluently. (I’m using the word ‘expat’ on purpose here, more on that later).

I’ve never considered myself “one of those expats” — meaning one who has lived in Berlin for several years but still struggles to order coffee auf Deutsch. I speak German fluently (yes, being Dutch helps) and I’ve worked jobs that are at least partly in German and require in-depth knowledge of German politics and society.

Still, I spend a good 90% of my days speaking, reading and writing in English. Most of my friends are native English speakers (or equivalent) and despite my goal to read at least one German book a month, I keep reverting back to my big ‘to-read’ pile which is, you guessed it, mostly in English. Oh, and I’m currently sitting at a café that only has an English menu and the language I’m writing in is… right. Maybe I’m not that different after all.

***

In an Instagram-live-conversation-turned-book titled English in Berlin3, artist Moshtari Hilal and political geographer Sinthujan Varatharajah talk about this phenomenon.

Both Hilal and Varatharajah grew up in Germany with immigrant parents — from Afghanistan and Sri Lanka, respectively — who had no choice but to learn German. They point out that when Tamil or Arabic is spoken in a public space, this is seen as a problem, a sign that a “parallel society” is being created. The ubiquitousness of English, however, is seen as a by-product of globalization, not something to question.

Hilal describes going into a shop where the saleswoman doesn’t speak German. She switches to English, not wanting to insist they speak German — as if that’s the only legitimate language to speak in a public space— but she feels uncomfortable. “Wow, you can work here without speaking German?,” Hilal thinks to herself. “My parents didn’t get any work because they couldn’t speak German! And this rule doesn’t apply to you all of a sudden?”

“English is accepted as the legitimate alternative in some spaces and places,” Hilal continues, “without being seen as a parallel society.” While English-speaking expats aren’t required to speak even the most basic level of German to be hired at a service job, other migrants (meaning non-white and/or working class people) have to be fluent just to exist in Germany in the first place.

Varatharajah emphasizes: “It’s not about ensuring the supremacy of the German language in public spaces. German is (…) an imperialist language that has been and still is violent.”4 Instead, they say, it’s about addressing this double standard and the racism and classism that’s behind it.

***

English is seen as an inclusive language, but is it, really? Inclusive of whom?

Many among the older generation in Berlin are bilingual; in German and Russian, that is. The Berlin Wall fell only 35 years ago, less than half a lifetime. Before that, kids in communist East Germany were taught Russian in school as their second language.

Besides Russian, languages most commonly spoken in Berlin are Turkish, Arabic and Polish. The people speaking these languages often don’t speak English, or not fluently. However, during the pandemic, Hilal and Varatharajah write, signs at pharmacies or government websites often displayed crucial health information in German and English only — thereby excluding a large group of people.

Clearly, English is not the language most people in Berlin are fluent in, but it is the language of the middle class and of (cultural) capital. If inclusivity is the goal, English is not the way to reach it.

***

I’m learning Turkish for a variety of reasons, mainly to be able communicate with people when I travel through (rural parts) of Türkiye later this year. It’d also be fun to understand the lyrics of that Acid Arab song that I’ve had on repeat lately.

As I make my way through my Turkish lessons, going over the same basic phrases again and again (I learned that yine anlamadım means “I still don’t understand”) I am reminded of the effort it takes to learn a new language. It requires resources — time, money, a sense of mental clarity — that, for many people, are not so easy to come by.

In the last weeks, I’ve been reflecting on my own hesitancy to speak German on a more regular basis. Language is power. If I can express myself well, I have the upper hand in the conversation. I can make jokes or nuanced observations. I can show you the version of myself I want to you to see.

Learning a language, on the other hand, means making mistakes. It requires vulnerability. And patience, both from you and your partner in conversation. Speaking English, then, is also a ploy for efficiency. We save time when we talk in a language we all understand well enough, even if none of us are native speakers — and often times, efficiency is valued more than deep understanding.

***

When I complain about the lack of Dutch being spoken in public places in Amsterdam, my frustration is not so much aimed at the individuals who, for whatever reason, approach me in English. What bothers me is the lack of broader societal resistance to this trend. How self-evident it has become.

Of course, it’s a far-right nationalist narrative that tells people to “learn the language or leave”— which is rampant both in the Netherlands, where a far-right government currently holds power, and in Germany, which is sliding into the same direction with terrifying speed. Like the writers of English in Berlin, I’m therefore hesitant to make the case in defense of these imperialist languages.

But I do worry that our tendency to revert to English deprives us of a certain sense of specificity. After all, the word ‘global’, besides referring to something that is world-wide, can also be taken to mean something general. What do we lose when we trade a local language for an international version of English?

Context, for a start. In particular around politics and activism.

For example, when the Black Lives Matter movement gained global support in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in 2020, Germany also saw a wave of protests. However, as Hilal and Varatharajah point out, German media used examples from the US to talk about racism and police violence— as if there were no local cases to be found (needless to say, there are many). A global solidarity movement against racism is important, but how can we address local issues when we don’t understand what is going on here?5 And how can we understand when we don’t speak the language?

***

Five weeks into my Turkish course we do an exercise in the style of ‘guess who’ — figuring out which character someone has in mind by asking questions like “is he Çiğdem’s father?” or “is she Cem’s sister?”. When I try to speak freely, without using my book, I stumble. I’m lost for words. I look them up. I try again.

Learning a language is not easy. It’s an investment. It’s an act of care. It shows that you aren’t just passing through — you are acknowledging who and what was there before you. In contrast, living somewhere without learning the language seems careless to me.

Language is a tool. A tool of oppression, undoubtedly, but also a tool of agency. If we learn about a place’s language, history and culture we can position ourselves within it and maybe, if the moment calls for it, exert our influence to change it. I feel like it is up to us — the migrants that are called expats, who chose to move somewhere not because we needed to but simply because we felt like it — to make that effort. Language isn’t everything, but it’s a start.

***

Later that week I go on a date. She’s a writer and, since I’ve been asking to read some of her work, she has brought me a copy of her poetry book. Back home, as I flip through the pages of poems written in German as well as some Russian, it dawns on me that we’ve been speaking English this whole time. I’m not sure why. (Or maybe I do; the aforementioned ‘wanting to show the best version of myself’.) What a shame to get to know a person — someone who works with words, no less — in her third language and my second. I wonder who she is auf Deutsch.

“Es ist mir gerade etwas eingefallen…” I start a voice note to her. “Let’s switch to German?”

Thank you for reading! I consider writing a collaborative act - everything I write is informed by everything I’ve read, the conversations I’ve had and the places I’ve visited. If you have any thoughts or questions, I’d love to hear them.

Having said that, Turkish does have a Latin-script alphabet and only a few letters are different from the German alphabet — it would be an entirely different story if I was learning Arabic or Japanese, for example.

Interestingly, the book contains both the original German transcript of the Instagram conversation and its English translation. I made a point of reading the German version, but am (ironically) quoting the English here. Either way, I recommend. You can find it here.

This applies to Dutch and English too, of course.

The language aspect is so fascinating. It’s true that we don’t treat all languages the same, and English speakers get away with stuff Chinese, Arabic, Bengali, or Turkish speakers would not. It’s all part of this massive tangle of supremacy we’ve all taken on by osmosis.

Loved this! I am an immigrant in the Netherlands, and just started my A1 course. I’m shocked how many people in my class have been here for 3-7 years and only now starting- and only because their job requires it. Like, living here, engaging with the culture, building community: shouldn’t THAT be what makes you want to learn?